It’s not the strongest of the species that survive, nor the most intelligent, but the one that is most responsive to change.

Charles Darwin

Companies have a fairly predictable life cycle. They start with an innovation, search for a repeatable business model, build the infrastructure for a company, then grow by efficiently executing the model.

Over time, innovations outside the company (demographic, cultural, new technologies, etc.) outpace an existing company’s business model. The company loses customers, then revenues and profits decline and it eventually gets acquired or goes out of business. (Looking at the Dow-Jones component companies over time is a graphic example of this.)

Over time, innovations outside the company (demographic, cultural, new technologies, etc.) outpace an existing company’s business model. The company loses customers, then revenues and profits decline and it eventually gets acquired or goes out of business. (Looking at the Dow-Jones component companies over time is a graphic example of this.)

Creative Destruction

If you’re an entrepreneur, you spend your time worrying about how to get out of the box on the left and move to the right. You want to start executing the business model.

Ironically, the best CEO’s in the box on the right are constantly worrying not only how to execute but also how to remain innovative and entrepreneurial.

Ironically, the best CEO’s in the box on the right are constantly worrying not only how to execute but also how to remain innovative and entrepreneurial.

Innovation and Entrepreneurship in the Enterprise

How large companies can stay innovative and entrepreneurial has been the Holy Grail for authors of business books, business schools, consulting firms, etc. There’s some great work from lots of authors in this area. (A short list at the end of this post.)

Over 15 years ago, Clayton Christensen observed that there are two types of innovative strategies for a large company – sustaining and disruptive innovation. He believed that large companies handle sustaining innovation – evolutionary changes in their markets, products, etc. valued by their existing customers – fairly well. But most large companies find it hard to deal with disruptive innovation – radical shifts in technology, customers, regulatory changes, etc, that create new markets.

Sustaining Innovation and Entrepreneurship in the Enterprise

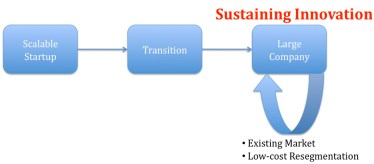

If we use our “startup to large company,” diagram, we can see that sustaining innovations occur within a large company’s existing management structures. I’ll offer that the diagram looks something like this.

If you’ve been reading my book on Customer Development and follow my work on Market Type, this type of innovation is best for adding new products to existing markets.

If you’ve been reading my book on Customer Development and follow my work on Market Type, this type of innovation is best for adding new products to existing markets.

Disruptive Innovation and Entrepreneurship in the Enterprise

Yet most research has shown that disruptive innovation, that is innovations that go after new markets, new customers, new technologies, etc. are best built outside a large company’s existing organization.

This type of organization is best for finding new niches in existing markets or creating entirely new markets. Why? Disruptive innovation in a large company is attempting to solve two simultaneous unknowns: the customer/market is unknown, and the product feature set is unknown. Just like a startup.

This type of organization is best for finding new niches in existing markets or creating entirely new markets. Why? Disruptive innovation in a large company is attempting to solve two simultaneous unknowns: the customer/market is unknown, and the product feature set is unknown. Just like a startup.

The diagram for managing disruptive innovation in large company looks suspiciously like starting from square one as a startup.

What’s Missing in Innovation and Entrepreneurship in the Enterprise?

After growing past their scrappy startup roots, large companies trying to master disruptive innovation face the ultimate irony; “the Innovator’s DNA” that’s needed has more than likely been purged from the organization. Mastering disruptive innovation in a large company requires:

– different people

– different processes

In fact the people a large firm needs for this kind of innovation looks suspiciously like startup founders and the processes needed look like Customer Development.

Customer and Agile Development (and the Lean Startup) may be the emerging methodologies large companies need to build innovative new products.

More in future posts.

Lessons Learned

- Innovation in large company’s come in two forms; sustaining and disruptive

- Disruptive innovation in a large company may require processes and individuals that look a lot like those in a startup.

- Customer and Agile Development may be the methodologies that large companies need to build innovative new products

Further Reading:

Harvard Business Review Articles

– Meeting the Challenge of Disruptive Change, Clayton Christensen/Michael Overdorf: March/April 2000

– The Quest for Resilience, Gary Hamel/Liisa Valikangas: Sept 2003

– The Ambidextrous Organization, Charles O’Reilly/Michael Tushman: April 2004

– Darwin and the Demon: Innovating Within Established Enterprises, Geoffrey Moore: July/August 2004

– Meeting the Challenge of Corporate Entrepreneurship, David Garvin/Lynne Levesque: Oct 2006

– The Innovators DNA, Jeffrey Dyer, Hal Gregersen, Clayton Christensen: Dec 2009

Books

– Innovators Dilemma & Innovator Solution, Clayton Christensen

– Winning Through Innovation: a Practical Guide to Leading Organizational Change and Renewal, Charles O’Reilly

Filed under: Corporate/Gov't Innovation, Customer Development |

You hit it on the head–even when large companies realize that they need to set up new divisions to pursue disruptive innovation, they usually burden the new divisions with the same policies and procedures as the parent corporation. They also tend to populate the new divisions with people from the parent organization who are fully inculcated with the parent organization’s policies and bureaucracy. The result is that these new operations rarely come up with the discontinuous/disruptive innovations that the parent company was looking for. If, through some miracle, they succeed, the innovations are rarely adopted by the parent company.

[…] dilemma. In his latest post, serial entrepreneur, B-school professor, and diagram impresario Steve Blank outlines the difficulties of continuing to innovate as your start-up transitions into a stable […]

I’ve read your excellent book and recently read “The Power of Pull” by Hagel, Brown and Davidson. The Power of Pull offers the keys to innovation in the DNA of Startups and Enterprises as well, but I believe it is almost impossible for Enterprises to recapture their innovation spark after they cross over to the Enterprise threshold, unless the company is managed by dominate CEO who can impose his vision, for example Apple, otherwise the only way to survive is acquire startups to get into new markets. Even after acquiring innovative startups the people who created the company most likely will leave after a short period based on their contact.

Enterprises need to become leaner and allow more freedom for their employees to innovate by using resources outside of the enterprise. Individuals and groups should be measured and rewarded based on their output of production and/or ideas. Even if those ideas don’t produce measurable results in the short term. Enterprises have to become learning enterprises using the processes described in your book.

Nice post. Christensen’s book certainly has some timeless insight on this topic as well.

In thinking about the changes that small companies undergo on the way to becoming large, I found it also interesting to consider how institutional memory tends to forget the basic economic concept of sunk costs. As companies invest more and more money into a given technology, process or initiative, it becomes increasingly difficult for management to stop the bleeding and change direction – this is where small, highly adaptive companies are able to disrupt the market with something that a large company could never pull themselves to consider.

Steve, I absolutely agree that large organizations need to shift towards processes that look like Customer Development.

There are a couple of obstacles preventing larger organizations to implement this shift, however. They overlap with more general differences between the structures and attitudes of start-ups and big corps:

* Risk

Large corps are generally risk averse, while start-ups are all about taking on (and hopefully managing) risk. This can be tracked back to individual risk taking and processes. A start-up entrepreneur knows he is embarking on a risky venture and he/she will do all he/she can do manage that risk and grow. A manager in a large corp often has little incentives to take on risky intrapreneurial projects, since that could hamper his/her career.

* Size

A large corp expects new projects to quickly generate very large revenues. If Nestlé, for example, launches a new project, then a first-year revenue of 10 million USD will be seen as a failure. For the usual start-up that would often represent quite a success. The problem with innovative products/services and business models is that they often take some time to grow to generate substantial revenues and profits.

* Experimentation

Start-ups experiment with their business model in an iterative fashion until they find the most appropriate model for success and growth. Structures in large organizations mostly favor the big bang approach, which aims to quickly generate large revenues with a “proven model”. This is sometimes related to a sort of “resource-course”. Start-ups don’t have the resources for a big-bang approach and experimentation is thus often a practical byproduct of the entrepreneurial journey. Large corps have the resources to start big, which might not be such a good thing after all… They have to come to understand and value business model prototyping and experimentation, which might require slightly more time than the quarterly reports demanded by stock markets…

In my client work with large organizations around the world I am still trying to find the best way to “sell” a more iterative approach. I do try to get them to mimic start-ups in order to move towards a more iterative approach of business model innovation. To date the most successful argument is “risk management”. I convince companies that it is almost impossible to immediately find the right new business model in a new market. I order to manage risk they need to prototype to slowly, but constantly converge towards a successful model…

Steve,

It is more or less clear why enterprise might want to attract the startup folks into there fold. But what is in it for an entrepreneur? How would the risk-reward formula work? Hire an entrepreneur at the minimum wage and give him a multi-mega-dollar stock earn-out deal?

Looking fw to ideas on this in your follow-on posts

Misha

It’s worth considering why disruptive innovations are best pursued by large companies in autonomous units. For Christensen, a disruptive technology underperforms against attributes that are important to a large company’s core customers, but delivers value against different attributes that are important to a new set of customers (and that are unimportant to the large company’s core customers). Hence, consistent with your definition of disruption, we have a new technology serving a new market. This negates the major advantage that large companies have over startups: their control over lots of resources in R&D, production, marketing, sales, etc. The autonomous unit can have its own R&D function, because the new technology is not closely related to the parent’s core technologies. Likewise, the autonomous unit can have its own production function, and it can have a separate sales & marketing staff, because it serves a different set of customers. In short, as you point out, the autonomous unit looks just like a startup — and should staff itself and manage its processes accordingly!

So, customer development/lean startup is a great template for large companies pursuing truly disruptive innovations, i.e., those involving new technologies and new markets that do not draw heavily on the parent’s existing resources. CD/LS disciples may try to stretch the template to encompass sustaining technologies. My intuition says that some CD/LS concepts do make sense for sustaining innovation. In fact, the CD/LS framework shares several precepts (e.g., rapid prototyping, intensive user feedback) with “design thinking,” which is used by many large companies to develop sustaining innovations. An important challenge for our community is to figure out how CD/LS differs from design thinking.

Big companies can also get a good deal on innovation when the entrepreneur fails the find a business model and the VC’s shut down the company and sell off the IP to get some of their money back. I heard that Microsoft bought Vivaty’s IP and took on their technical staff when the VC’s shut Vivaty down.

[…] a strong will to succeed, then there should be able to help your large organization continually find opportunities for innovation. These steps were adopted by the work of Peter Drucker and the more recent work of Eric Ries and […]